Editor's Note: This article was written with support from the team behind This Climate Does Not Exist. See end of post for the complete list of team members.

This past August, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its latest report and the message is clear: the human-induced climate crisis is well underway and scientists are sounding ‘code red for humanity.’

Indeed, heavy rainfall swept across Germany and Belgium in July 2021, causing several rivers to flood. This triggered major landslides and buildings to collapse and led to hundreds of casualties. A recent attribution study suggests climate change was implicated in these deadly floods and that these events will become more frequent as global temperatures increase. This year also saw countries around the world record their worst wildfires in decades. California’s active Dixie fire is being touted as the second-largest in the state’s history, burning nearly 1 million acres (4047 km2) to date.

Tackling climate change with empathy…and AI

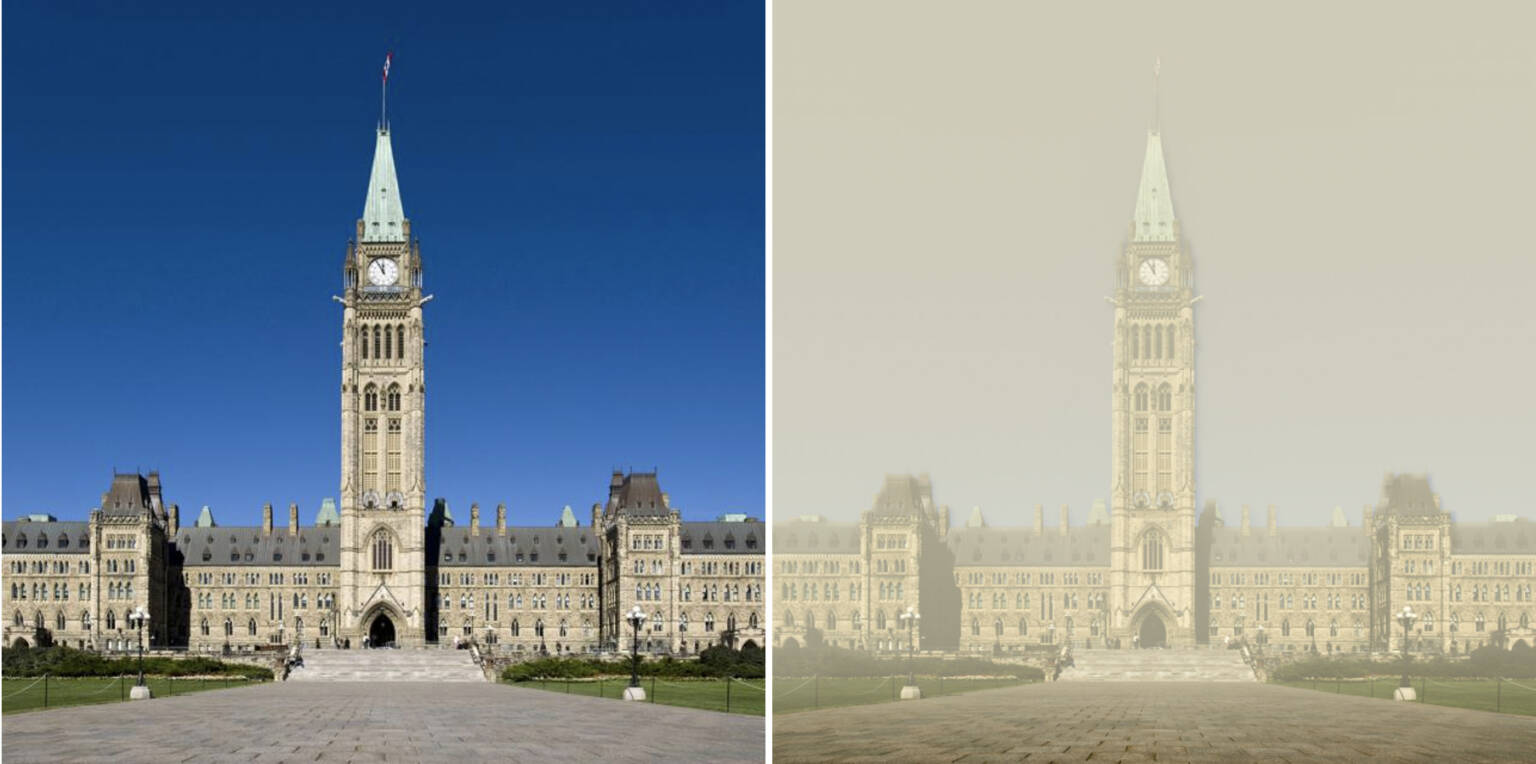

If climate change is happening right now, how can we increase public awareness and mobilize government intervention? Mila’s Scientific Director and Founder Yoshua Bengio pondered this question a little over two years ago when he envisioned the development of an easily accessible tool that would allow its users to imagine the impacts of environmental disasters anywhere in the world. Today, thanks to an interdisciplinary team of machine learning researchers from Mila, climate change experts, and collaborators, This Climate Does Not Exist has launched. It is an AI-driven virtual experience based on empathy that allows users to visualize environmental impacts—floods, wildfires, and smog—of the current climate crisis, one address at a time.

This Climate Does Not Exist was drawn from a growing trend that uses generative adversarial networks (GANs)—a class of machine learning frameworks that actually arose from Professor Bengio’s lab—to create full-colour, detailed images of virtually anything: cats, people, artwork, you name it.

But the name goes beyond this growing AI trend that mainly generates fakery for online amusement. It serves as a way to emphasize that, while a person might not be experiencing environmental disasters in their own backyard, everyone’s actions and involvement matter, as those events are happening somewhere else in the world and are expected to increase in frequency and intensity in the years to come. With an emphasis on the fact that the AI-generated images are not real, the team chose the name to try to trigger emotional reactions from people to increase their conceptual understanding of climate change and incite action.

How it Works

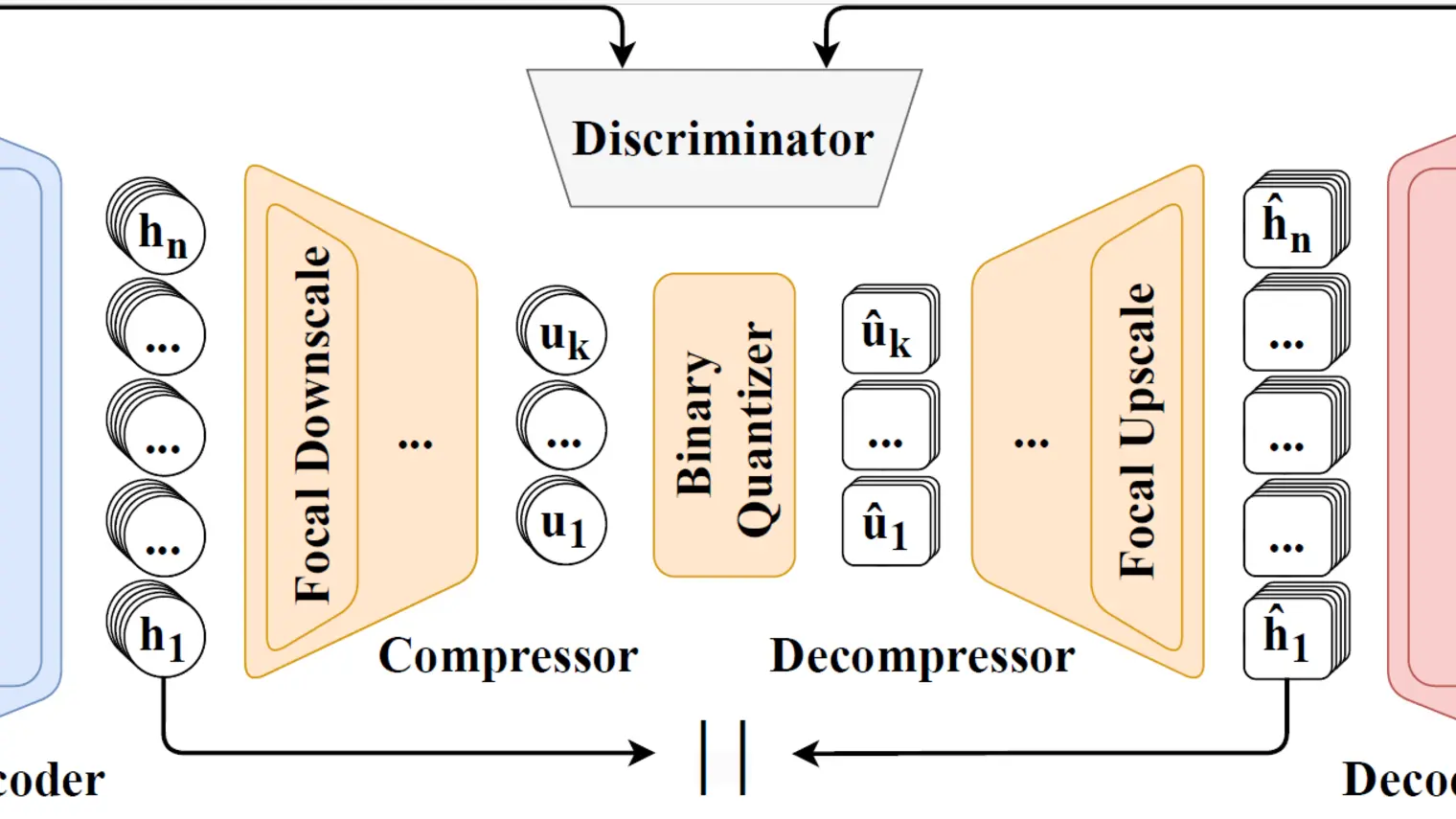

GANs were invented by Goodfellow et al in Mila’s hometown of Montreal in 2014, and are a class of machine learning frameworks that give AI the ability to generate new content. These AI models are made of two neural networks: a generator and a discriminator that are in constant competition with each other. The generator’s goal is to fool the discriminator by creating images that are as realistic as possible (e.g., flooded streets, smog-filled cities, or homes surrounded by wildfire smoke). The generator gradually improves its performance and increasingly fools the discriminator.

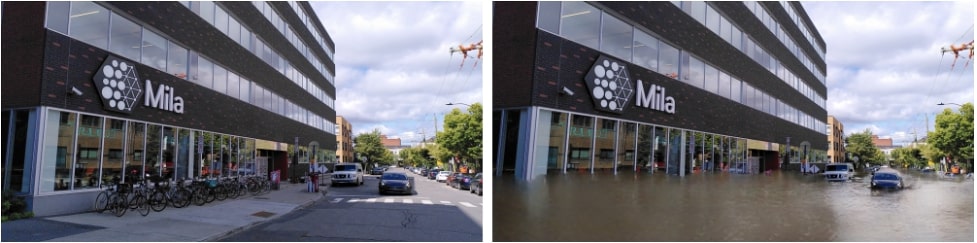

In just a few short years, GANs have evolved drastically and offer some of the most versatile neural architectures today. This project leverages the potential of GANs and other modern computer vision techniques to create lifelike landscape images that never existed while taking into account the relationship between surrounding objects like trees, hills, streets, or cars. For example, if a flood is simulated on the street where the Mila building is located, the model is able to generate the building’s reflection in the water and circumvent cars (see Figure 2).

Once on the website, the user is prompted to search for any address listed on Google Street View, offering suggestions such as their current or childhood home, workplace, or favourite travel destination. Yet, these suggestions aren’t random. They are locations that the user might have a sensitivity toward so that the image output prompts them to reflect on what they see on their screen.

The technical details of the algorithm have been recently posted as an arXiv preprint, ClimateGAN: Raising Climate Change Awareness by Generating Images of Floods.

Cognitive Bias and Climate Change

Prior to the launch, the team sent out a pilot version of the website to individuals outside of the project to gain feedback about their experience using the website and how it made them feel. Most respondents relayed sentiments of empathy. One user said: “Facing the hard truth virtually made me become more realistic about the consequences of climate change again.” Another respondent expressed similar sentiments: “It’s a thought-provoking exercise to realize how climate change could affect our daily lives.”

The reality is that the essence of the UN report has been repeated and known by scientists and climate activists for a long time: climate change is real and results from increased carbon emissions driven by human activities. Despite all the fact-based evidence, the alarming rise of natural disasters across the globe has not yet changed our individual behaviours and policies to sufficiently mitigate the climate catastrophe at hand. Cognitive biases can prevent individuals from taking action, especially when a climate change disaster is occurring in another part of the world, seemingly far away and undisruptive to their daily lives.

Psychological distancing occurs when climate change is not perceived as an immediate and direct threat to ourselves, with this perceived distance stemming from both time (since the worst effects of climate change are in the future) and space (since many of its effects happen far away from us). Research suggests that the realistic nature of photographic imagery—showing people images of the impacts of climate change—can help reduce this distance and enhance public engagement.

On the one hand, I felt sad because it reminded me of the unstoppable effect of climate change due to human acts. On the other hand, I felt motivated to act as much as I can and share the website with my friends to encourage them to take action and talk about this reality.

The ethos of ‘This Climate’ builds off this notion and presents an original use of AI. Here, AI is not applied to improve a specific technology or directly reduce emissions but rather to empower humans, raise awareness, and trigger empathy. This is especially important as discourses of climate delay—arguments used to justify inaction—increasingly pervade public conversations about the collective efforts and actions urgently needed to mitigate the gravity of the impacts of climate change. Harnessing AI to create images of personalized climate impacts has the potential to be markedly effective in overcoming these psychological and social barriers to action while also raising awareness.

Unwise and excessive technological optimism can be used to rationalize such discourses by assuming that technological progress (i.e., human ingenuity) will necessarily be good for society and deliver ground-breaking solutions to current and future threats to our collective well-being. The belief in such future magical solutions would simply justify the lack of actual action and lead to avoidance of the necessary but sometimes difficult decisions needed to mitigate climate change, short of a technological miracle. By empowering global citizens to rethink their cognitive biases and take action to find solutions thanks to the novel use of AI, ‘This Climate’ offers an opportunity to strengthen public discourse on climate change and emphasize social responsibility.

Today, research institutions, organizations, and activists are turning to AI and exploiting its potential to fight against climate change. Promising interdisciplinary initiatives that leverage AI for the benefit of the planet are rapidly cropping up. Such innovative projects at the intersection of AI and climate research have the potential to further support the efforts of citizens and their governments to protect our planet and future generations.

See for Yourself

Head over to ThisClimateDoesNotExist.com to visualize the impacts of climate change on places you hold dear.

Team

Project Leadership

Yoshua Bengio, Scientific director

Sasha Luccioni, Postdoc

Victor Schmidt, PhD

Machine Learning and Programming

Mélisande Teng, Intern

Tianyu Zhang, Intern

Alexia Reynaud, Intern

Sunand Raghupathi, Intern

Vahe Vardanyan, Postdoc

Nicolas Duchêne, Intern

Gautier Cosne, Intern

Adrien Juraver, Intern

Alex Hernandez-Garcia, Postdoc

Jason Ardel, Intern

Léopold Herlaud, Intern

Léonard Boussioux, App developer

Steven Bocco, App developer

Charles Guilles-Escuret, App developer

Mike Arpaia, Engineer

Shivam Patel, Intern

Sahil Bansal, Intern

Communications and Website Content

Marie-Claude Surprenant, Digital Strategist

Brigitte Tousignant, Editor

Caroline Brouillette, Content Advisor

Silvie Harder, Content Advisor

Climate Science

Karthik Mukkavilli, Postdoc

Ata Madanchi, Intern

Hassan Akbari, Intern

Vitoria Barin Pacela, Intern

Yimeng Min, Intern

Behavioral Science

Erick Lachapelle, Collaborator

Thomas Bergeron, Collaborator

Ayesha Liaqat, Intern